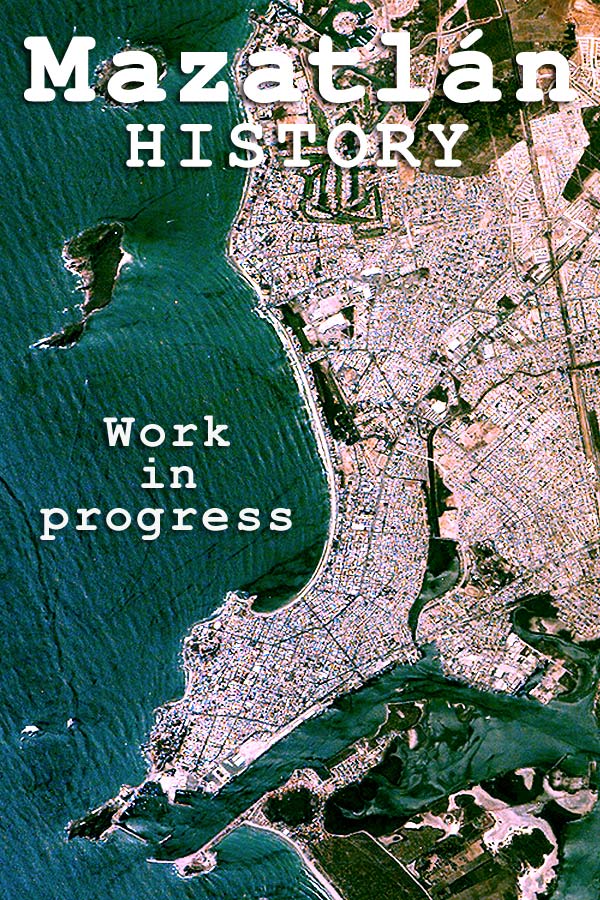

Mazatlan History from pre-Colonial times to the 21st century!

1500s | 1600s | 1700s

1800s | 1900s

Mazatlán today

Mazatlán is one of the oldest ports in the Americas, and one of the most historically fascinating cities in all of Mexico! Learn more about Mazatlán and its over 400 year history!

The name Mazatlan means Place of the Deer in Nahuatl, one of the languages used in our region of Mexico before the Spanish conquest.

The Totorames are believed to have lived in fixed locations -- including the area occupied by Modern Mazatlan -- and are also believed to have supported their communities primarily through fishing and agriculture, as well as collecting and trading salt with inland peoples.

Skilled craftsmen, the Totorames made decorative objects with pearls, shells and feathers, and were skilled potters.

History knows virtually nothing about Totorame spiritual practices, or political / societal organization.

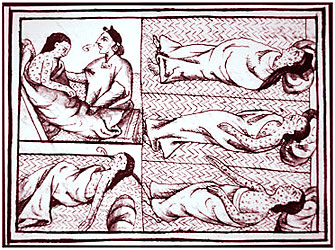

Sadly -- and unlike their inland neighbors the Toltecs and Aztecs -- the Totorames left no pyramids, large scale earthworks or buildings. Totorame civilization largely vanished when the Spanish arrived with their brutality and, more importantly, their diseases, for which the indigenous people of Sinaloa had no immunity.

In tangible ways the history and spirit of Totorame culture survives.

Exquisite Totorame pottery adorned with elaborate designs indicative of an evolved and sophisticated pre-Columbian American culture can be seen at Mazatlan's Museo Arqueologico, the archaeology museum located in the Centro Historico.

These artistic expressions of the Totorame soul speak directly to contemporary viewers and are reminders that the history of Mazatlan did not begin with the arrival of the Spanish.

The Spanish invasion of the Americas in the 16th Century -- though foretold by vaious cultural myths -- was a massive shock to pre-Columbian cultures throughout both north-central and South America.

This was no more so than in Mexico, which was the tip-of-the-spear of the attempted Spanish colonization of several parts of the Western Hemisphere.

After Hernan Cortez rapidly conquered the Aztecs at present-day Mexico City in 1521, his Conquistadors met little resistance as they began their outward expansion from south-central Mexico and began subjugating more of the indigenous peoples of present-day Mexico.

In the earliest years of the Spanish conquest, Indian tribes near Mazatlan most likely knew nothing of it -- 1500s communication over long distances in Mexico was tenuous at best -- but the storm that would rage through Sinaloa was brewing. In 1531, just 10 years after the conquest of Mexico City, a renegade commander, Nuno Beltran de Guzman reached the Pacific coast of Mexico with substantial forces and marched through Sinaloa with a private army, destroying and pillaging indigenous communities along the coast -- and inland when possible.

History reveals that more destructive than the military behavior of Beltran de Guzman and his Conquistadors was the simple fact that they carried European diseases for which local populations had no immunity.

Indigenous Sinaloan communities were decimated by disease: it is estimated that over just two years -- 1535-1536 -- Totorame and Cahue populations fell by an astounding 90%. Sinaloa was left substantially depopulated -- a vacuum that Spanish warriors and later migrants were only to happy to try to fill.

During these earliest years of the Spanish conquest of Sinaloa, the region currently occupied by the municipio (municipality) of Mazatlan was called Chamelta, after the name of the nearest Spanish garrison. Founded in 1531, Chamelta was soon abandoned as a result of continued Indian raids and Mazatlan's port and surrounding countryside remained free of Spaniards, if not their diseases, which traveled as a result of interaction between infected Indian communities.

But an even greater Spanish presence was on the horizon.

Beltran de Guzman's marches through Pacific Mexico were followed by those of second-wave Spanish Conquistador Francisco Ibarra.

In 1565 -- instantly following the discovery of gold and silver in the Sierra Madre foothills surrounding Mazatlan -- Francisco Ibarra arrived in Sinaloa and founded the towns of Copala and Villa de San Sebastian (now Concordia), at the start little more than Spanish military support bases for early mining operations in Sinaloa.

Ibarra also rebuilt the garrison at Chametla, and claimed the entire region for Nueva Vizcaya. The administrative districts under his jurisdiction included the villages of San Sebastian, Copala, and Panuco and, at least nominally, the Port of Mazatlan.

In 1576, Don Hernando de Bazán, Governor and Captain General of the Spanish Province of Nueva Vizcaya, authorized Captain Martin Hernandez to occupy and settle parts of Chamelta -- including the site of Mazatlan, granting him titles to land in return.

Martin Hernandez marched to Chamelta with his family and a number of soldier / adventurers and the permanent Spanish presence in Mazatlan began.

In the late 1580s Spain and England were at war, and one of the tactics both sides used was to grant "charters" to "privateers" -- essentially making them state-licensed pirates -- to raid each others possessions in the New World.

His goal was to capture the Manila Galleon Santa Ana when she returned from the Philippines.

Manila Galleons were large Spanish cargo vessels that sailed between ports on the western coast of New Spain to Manila in the Spanish East Indies, now the Philippines. They transported silver mined in Peru and Mexico and traded it for spices, silk, gold and other high-value merchandise that they carried back to conquistadors and colonists New Spain.

Nicknamed "The Navigator", Cavendish was attempting to duplicate the successes of Sir Francis Drake, who raided and pillaged Spanish towns and ships in the Pacific on his circumnavigation of the globe in 1578.

Cavendish arrived in southern Sinaloa from England with three vessels: his flagship Desire, a 120 ton warship armed with 18 cannon; the 60 ton Content armed with 10 cannon and a 40 ton supply ship, Hugh Gallant.

Cavendish sailed up the Sinaloa coast in September 1587 and arrived at Mazatlan, anchoring his small fleet off Deer Island to do maintenance on the ships, replenish supplies and wait for the Santa Ana -- all the while being observed by Spanish horsemen from the villa of San Sebastian de Chametla.

Repaired and re-stocked, Cavendish made the short voyage across the Sea of Cortez to Cabo San Lucas and on Nov 4, 1587, spotted and ran down the Santa Ana after a several hour chase.

As the Desire drew alongside the Santa Ana and boarded her. Fierce hand-to-hand combat erupted and the initial attack was repulsed. The Desire then began firing her cannon and rammed the Santa Ana, with some shells piercing her hull below the waterline, and English sailors boarded the ship once more.

Captain Alzola knew that the Santa Ana was sinking and surrendered.

Estimates vary, but many historians put the loss to Spain at between 500,000 to 800,000 pesos, and all agree that it was the largest loss suffered by a galleon during the over two hundred years of Acapulco - Manila trade.

Cavendish burned the Santa Ana and left her crew and passengers in Cabo with some supplies. The survivors managed to re-float the wrecked ship and limped across the Sea of Cortez to Mazatlan and then south to Acapulco.

Cavendish continued westward and sailed across the Pacific, returning to England in 1588 a wealthy hero destined to become a permanent fixture in English maritime history.

Word of his exploits spread and pirates and privateers worldwide took note: the harbor at Mazatlan was a great place to hide if you wanted to ply your trade in the Sea of Cortez.

"Mazatlan" was first mentioned in 1602 in military communications to the Spanish government.

But it wasn't present-day Mazatlan.

The communication referenced a small village, San Juan Bautista de Mazatlan (now Villa Union), 30 miles southeast of The Pearl of The Pacific. The modern history of Mazatlan really begins the early 1600s: in response to pirate activity the Spanish colonial government established a small garrison in present-day Mazatlan.

Thus began a multi-generational struggle between Spanish colonial naval forces and pirates that lasted through the 1600s -- and the 1700s as well.

Mining was beginning to play a role in the development of Mazatlan.

Significant silver deposits were discovered by Spanish adventurers in Sinaloa in the latter 1500s and early 1600s that were producing a substantial annual tonnage of precious metals and minerals. Mountain mining communities near Mazatlan like Concordia and Copala and the deep-digging at flatter mining locations like El Rosario were all in operation by the mid 1600s.

The size and number of mines increased substantially in 1600s, usually with Indians working as de facto slave labor in Sinaloa mines alongside black slaves from Africa.

As the tonnage of mineral treasure produced by these and other Sierra Madre mining towns near Mazatlan increased, hauling heavy loads east through the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains on crude trails or overland down the coast to Acapulco became increasingly impractical.

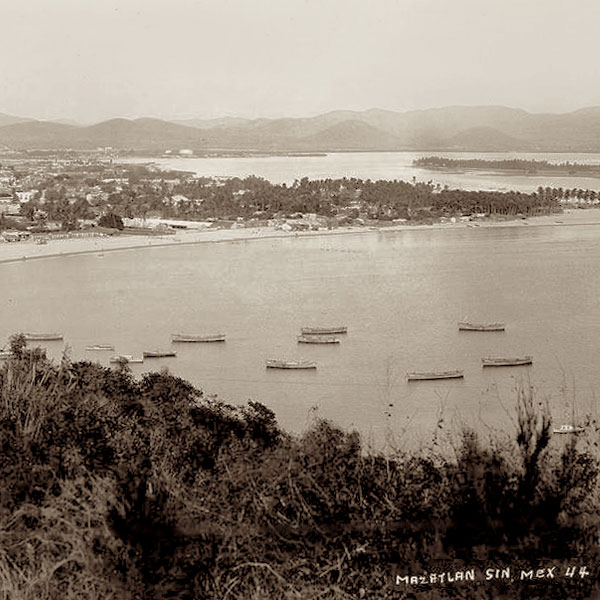

The Mazatlan port is one of the most spectacular natural harbors anywhere in the world. Beautifully sheltered from storms and deep enough to accommodate any 1600s ship, it is the premier natural anchorage on the west coast of Mexico.

Despite the pirate threat, the harbor at Mazatlan simply had to be utilized.

The 1600s mark when sea trade enabled the birth of Mazatlan, and sea trade enabled its increasingly important role in the history and economic development of Sinaloa State.

But despite the now-permanent Spanish presence, our city in the early 1600s was little more than a magnificent often-empty natural harbor that English, Spanish and French pirates used intermittently as a hiding place from which to attack the treasure-laden galleons that sailed Mexico's western coast.

at the port

There are countless pirate stories about Mazatlan in the 1700s, but 1700s Mazatlan history wasn't just about pirates, it was about what they wanted to steal: the ever-increasing tonnage of gold and silver shipments coming from nearby mines like those at Concordia and Copala and El Rosario.

The crucial role that sea trade played in the economic development of Mazatlan and Sinaloa can not be overstated because, much like a cruise ship, every arrival was a mini economic boom: ships must be repaired and re-stocked with food and water; sailors need to be on dry land and perhaps see a doctor better than the "doctor" on board the ship; cloths need to be replaced; men who have been at sea want female companionship.

These commercial activities, and more, require permanent populations in ports and -- being a port on the Pacific Ocean -- Mazatlan began to draw sea traffic and immigrants from Asia in addition to those from Spain and other countries in Europe.

Awareness of Mazatlan spread worldwide, and it rapidly became the most active port and immigration portal in Sinaloa. The growing town absorbed and benefited from international influences and money that reached far beyond the Spanish Empire, and that would expand the economy of Sinaloa far beyond mining.

Commerce fed local wealth, and the 1700s in Mazatlan saw other signs of advancement: The Pearl of The Pacific got its first church and first proper jail.

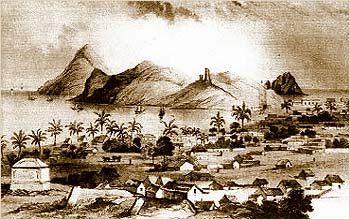

By the end of the 1700s the pirates were largely eradicated, but Mazatlan -- despite of over 200 years of foreign presence and its new church and jail -- was still little more than a far-flung colonial outpost and harbor surrounded by remnants of indigenous peoples whose occupation remained primarily subsistence fishing.

But eradicating the pirate threat allowed The Pearl of The Pacific to enter the new century strong, and begin to fulfill its historical destiny as Mexico's premier west coast port -- and one of the finest natural deep water ports in the world.

With the pirate threat substantially contained, the first decades of the 1800s in Mazatlan brought steadily increasing ship traffic and frequent arrival of passengers that hailed from very distant places.

Mazatlan had become one of the three most important ports on the Pacific coast of the Americas, the others being San Francisco and Valparaiso in Chile, with many ships arriving from Europe and the Middle East.

Much of this traffic -- an estimated sixty ships per year were arriving by the early 1800s -- was related to supplying mining operations in Sinaloa towns near Mazatlan, as well as bringing tools and materials that were used to continue to develop the city.

These long sea voyages were very dangerous: ships had to sail around Cape Horn or cross the Pacific to reach Mazatlan.

to the world

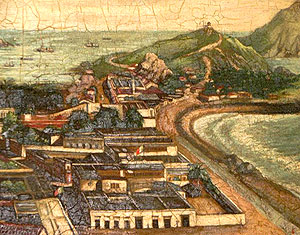

Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821 after an eleven year struggle, and growth in Mazatlan accelerated rapidly.

By 1836 Mazatlan had a population of between 4000 and 5000 non-indians, and thriving commercial relations with distant economies and peoples.

The commercial success of the port attracted the attention of of a wide range of European entrepreneurs -- primarily Germans, French and Spaniards -- who founded businesses that made them fortunes manufacturing cigarettes, cigars, matches, soaps, beer, carriages, candles and footwear.

But the attractions of the Port of Mazatlan extended far beyond Europe and fired the imaginations of businessmen as far away as Asia.

In 1829 a banker from the Philippines, Juan Nepomuceno Machado, arrived on a ship that had made the trans-Pacific voyage. He rapidly founded an import / export firm that traded with with vessels coming to our port from far-flung places such as his home country the Phillipines and other countries in Asia; Chile and Peru in South America; Europe -- especially Germany -- and the United States.

Once referred to as Paseo de las Naranjas (Orange Tree Walk) because of the orange trees that surrounded the space, the plaza quickly became a focal point for the community, and a place where Mazatlecos of all social classes gathered. Historically it served -- and continues to serve today -- as an icon of Mazatlan's cultural wealth.

Don Juan Machado's generosity and vision built upon an important civic infrastructure improvement that had been made in 1832.

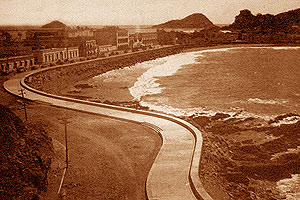

The area that the plaza occupies -- and much of what we now consider the Centro Historico -- was once a marshy estuary fed by the ocean. But in 1832 a sea wall was constructed along Olas Altas beach which dried the area and made it possible to construct larger buildings.

mid-1800s Mazatlán

In the mid-1800s the trade connections between Mazatlan and Germany enabled a tide of German immigration to The Pearl of The Pacific, with large numbers of immigrants arriving from Germany with skills and capital that she was waiting for, and who would shape Mazatlan history to this day.

These new citizens helped develop Mazatlan into a thriving commercial seaport and as a port-of-entry for men and equipment destined for the gold and silver mines of Sinaloa that were making nearby towns like Concordia, Copala, and Cosala some of the most prosperous communities not only in Sinaloa, but in all the Americas.

The industry of these German immigrants and their children is not just a footnote in history: it is felt in many ways in The Pearl of The Pacific, from our delicious German-derived beer, Pacifico, to street and plaza names and -- of course -- Banda music, which is closely related to polka.

Mexican-American war

The Mexican - American war of 1847 - 1848 resulted in the occupation of Mazatlan by American forces.

In early November, 1847, a United States Navy Squadron under the command of Commodore William Branford Shubrick arrived in the waters off Mazatlan and demanded that the port surrender.

The Mexican forces stationed in the city did not accept surrender, but did withdraw on the night of November 10th, ostensibly to save the city from the ravages of a fight.

On November 11, 1847, the USS Independence landed over 700 Marine bluejackets in Mazatlan under the cover of the combined naval guns of the squadron.

The city capitulated, beginning a nearly four month occupation that would last until March 6, 1848 when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war.

Nothing in the brief American occupation of Mazatlan -- which was relatively benign -- could prepare the citizens of Mazatlan for the nightmare of the two year French occupation of the port that was to come in the mid 1860s.

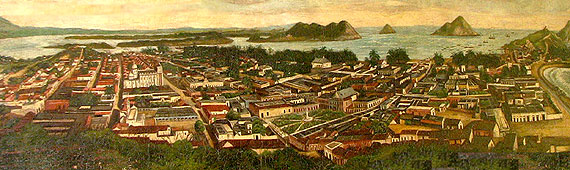

Prosperity drove development, and the amenities of a major city began to be more common in mid 1800s Mazatlan.

• The Mazatlan Times was an English language weekly that was first published by American A. D. Jones in 1863. The publisher claimed that his newspaper was the only weekly English language publication not only in Mazatlan and Sinaloa, but anywhere in Mexico.

• Icehouse Hill (Cerro Neveria) -- the promontory on your left as you travel from the Golden Zone toward Olas Altas Beach -- got its name at this time when tunnels that honeycomb the hill were used for storage of precious ice imported from San Francisco.

By the mid 1800s Mazatlan had become the largest and most rapidly growing economic and cultural center in Sinaloa, and served as the capital of Sinaloa from 1859 to 1873.

In spite of the economic and political ascendancy of Culiacan in the 20th century, many continue to consider the port to be the true cultural and spiritual capital of Sinaloa State.

in the early 1860s

Despite being the capital, mid-1800s Mazatlan history witnessed turbulent times, and the city was once again abandoned to foreign occupiers.

During France's Second Empire, under Napoleon III, an attempt was made to establish a protectorate in Mexico, which would have effectively made Mexico a French colony. This French attempt to colonize Mexico lasted from 1861 to 1867.

Variously referred to as the Maximilian Affair, the War French Intervention and the Franco-Mexican War, it was triggered by Mexican President Benito Juarez's suspension of interest payments to foreign creditors in 1861, which angered Britain, France and Spain, holders of most of Mexico's debt.

Maximilin I as he had proclaimed himself landed in Veracruz in May 1864, was initially received by enthusiastic crowds, and began extending his military reach inland -- and westward.

Historians generally agree that Emperor Napoleon III of France decided to act for a matrix of reasons -- some geo-political, some religeous -- but probably none more compelling than the fact that he wanted the silver that was being mined in Northwest Mexico. It is estimated that 4-5 million dollars of silver passed through the port at this time, a fantastically large sum in the 1860's.

As the capital of Sinaloa State and portal to the silver mines of Sinaloa State, Mazatlan made a tempting target.

Long before Maximilian arrived in Mexico and declared himself Emperor, warships from both the French and British navies had arrived off the coast of Sinaloa and were harassing merchant ships attempting to enter and exit the Port of Mazatlan and probing the city's defenses.

Mazatlan was the capital Sinaloa State in 1862 and the most important city in northwest Mexico, but Napoleon III wasn't focused on the political or propaganda benefits capture of the city might bring, this was about money.

The silver and gold coming out of Sinaloa's mines was the prize and the port was the key to securing it: Napoleon III was willing to commit substantial resources to take Mazatlan, whatever was happening in the Mexico City Theater of the Second Franco-Mexican War.

Commanded by French Vice Admiral Jurien de la Gravière, the corvette Bayonnaise was a formidable warship. Built in 1857, the she was a powerful three-masted craft that carried 30 cannon and a crew of over 220 sailors.

The Bayonnaise and Vice Admiral Jurien de la Gravière would remain a bane of merchant ships all along the Pacific coast of Mexico for most of 1862: her next port-of-call after San Francisco was Acapulco, where she began harassing commercial vessels on August 16th.

For a period, Mazatlan -- and Sinaloa State -- were spared further French attempts to disrupt trade, but that changed dramatically on March 26, 1864.

waters off the port

On March 26, 1864, the French flagship La Cordelière appeared off the coast of Sinaloa near Deer Island just off what is now the Golden Zone / Zona Dorada, and was soon joined by the British Pearl Class sail-steam corvette HMS Charybdis.

The arrival of the La Cordelière at Mazatlan was not a surprise: earlier in the month she was sighted prowling the waters off Nayarit State just south of Sinaloa and had captured a Mexican-flagged boat coming from San Francisco, California, that was carrying letters intended for deposed-President Benito Juárez.

The defensive strategy and fortifications at Mazatlan had been designed by Colonel Gaspar Sánchez Ochoa, a veteran Mexican army officer who had served under General Ignacio Zaragoza during the Mexican triumph at First Battle of Puebla on May 5,1862.

Colonel Sánchez Ochoa was an optimist: he thought that the French could be defeated at the waterline -- and that he knew how to do it.

On the afternoon of March 26th the La Cordelière put out a small landing craft which approached to within about 400 yards of the shoreline before drawing cannon fire from Mexican troops positioned at the beach she was heading for. The french landing craft returned small fire and the La Cordelière answered with her cannon.

The single landing craft withdrew unscathed, but there were injuries among the Mexican troops from as a result of near-misses and explosions of shells from the naval guns.

The skirmish had been a probe: the French wanted to see the Mexican artillery in action before making a serious attempt to land troops.

March 27th was quiet, with both sides preparing for a fight. Onboard the La Cordelière French Marines for a beach landing and ashore Colonel Gaspar Sánchez Ochoa and his second-in-command Captain Marcial Benítez prepared their troops, particularly the artillery, which Sanchez Ochoa hoped would sing or disable French landing craft before the reached the shore.

On March 28th the La Cordelière, still anchored off Deer Island, put out 14 landing craft that began to cautiously move toward the beach.

When the French boats were about a mile from the shore the La Cordelière began firing her naval guns at the artillery positions that had been identified two days before. Captain Marcial Benítez ordered his battery to return fire, but the six shells the Mexican gunners fired missed the La Cordelière.

Eleven of the landing boats made a dash towards the beach and managed to disembark their troops without casualties. The French marines now had a beachhead in Mazatlan, but it wouldn't last long.

With Captain Marcial Benítez continuing to direct artillery fire at the three landing craft that remained offshore, Colonel Sánchez Ochoa and his infantry troops attacked the French who who had made it to the beach.

After a fierce sharp firefight, the French re-boarded their landing craft and fled back to the La Cordelière, carrying several dead and wounded marines.

Colonel Sánchez Ochoa's troops had also taken casualties on the 28th: one dead and three wounded.

The 29th and 30th were quiet, with the French apparently trying to decide whether to attempt another landing. They decided not -- they would punish the Mexicans from afar.

At 2:00 pm on March 31, 1864, the La Cordelière turned broadside toward Mazatlan and opened up with all of its cannon on the side of the ship facing the city. The firing was largely indiscriminate and aimed less at the Mexican artillery positions than at the town in general.

By sunset the La Cordelière had fired between 300 and 400 shells -- the historical record is unclear -- while the Mexican artillery had fired 158 times.

Colonel Gaspar Sánchez Ochoa and his men had won the battle: the French would not attempt another beach landing. But the war -- and the suffering of the populace of Mazatlán -- was just beginning.

What followed the battles of March 26 to March 31 was a more than seven month naval blockade of the port by the La Cordelière and other French warships, the hardships of which created substantial dissent between Republican and Imperial factions within the population and caused Mazatlán to fall to the French Imperial Army in November, 1864.

The French blockade of caused great hardships for the people of Mazatlan.

Sea trade -- the foundation of Mazatlan's economy -- was completely disrupted, and only a small fraction of the products produced near the port could be transported out overland.

The populace of Mazatlan was divided.

Officially, the city was controlled by supporters of deposed-President Benito Juárez, but this civilian leadership was fragmented between several competing pro-Juárez factions, paralyzing city government and effectively ending the few city services that existed prior to the intervention.

A substantial fraction of the citizens didn't care whether the Juaristas or the Republican forces won -- they just wanted the war to be concluded as rapidly as possible so that commerce could be re-started.

Added to this dysfunctional mix were the substantial number of Mazatlecos who were monarchists who, openly or covertly, hoped for a French victory in the Franco-Mexican war.

One of the more colorful characters in Mazatlan history, Plácido Vega was a direct descendant of Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne and a 13th generation descendant of Cristopher Columbus.

A native of Sinaloa born in El Fuerte in the northern part of the state in 1830, Vega's family had been granted vast tracts of land and gold and silver mines. Unlike many Mexicans born to wealth in the mid 1800s, Vega somehow managed to grow up liberal, and had been an early and strong supporter of both the Reform Constitution of 1857 and of Benito Juárez.

Plácido Vega was a former governor of Sinaloa State -- he had been appointed in 1859 at age 29 and served until 1862 -- and had formal military training. Under his leadership, Mazatlan remain relatively calm in the earliest months of the blockade.

But his friendship with Benito Juárez was going to deprive Mazatlan of his leadership: in mid 1864 Juárez sent Plácido Vega to the United States on a secret mission to seek support -- and raise funds for -- the Constitutionalists fight against the French.

With Vega out of the picture, open conflict between two Juárez supporters -- Jesus García Morales and Ramón Corona -- broke out in October 1864, disunity that led to the fall of Mazatlan to the French.

The two intensely disliked each other for a variety of reasons, not the least of which was that Morales had attempted to have Corona brought up on misappropriation-of-state-funds charges when he was governor.

The long and bitter history of personal animosity between Morales and Corona would be the beginning of the undoing of the defense of Mazatlan.

On October 11, 1864, Corona marched 600 infantry soldiers and 200 of his cavalry -- he had an additional 1000 men in reserve -- to the edge of Mazatlan and demanded that Morales surrender control of the port to him.

Morales had just 500 men under his command, but he also controlled Mazatlan's artillery, 48 heavy cannon. Refusing to surrender, Morales had his men turn all of the guns around -- they had been pointed in the direction of the Sea of Cortez and the French -- and re-sighted them on the land approaches to the city and Corona's army.

At 2 am on October 16th, 1864, Corona launched an all-out assault from his positions south of the Centro Historico.

After a brief but intense battle, Corona's troops overwhelmed Morales' positions, with Morales being captured by Corona, personally, and over 35 Republican soldiers lying dead and wounded in the streets of Mazatlan.

Informed of the chaos in the streets of Mazatlan, Sinaloa Governor Antonio Rosales decided that he needed to act.

Arriving in Mazatlan in late October he managed to gain control of the city, but he was in for a surprise: the bloodletting between the Juarista factions had shifted public sentiment and many Mazatlecos simply wanted to surrender to the French and go about re-building their lives.

on November 13, 1864

On the October 24, 1864, three French warships, the D'Assas, Diamant and Victoire left Acapulco harbor loaded with a substantial compliment of fighting men.

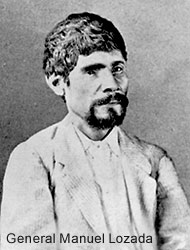

Lozada's Imperialist army's ranks had been swelled by the arrival of several hundred Cora Indians from the rugged mountainous part of northern Nayarit State, a tribe who fiercely resisted Christian conversion who had a long history of warfare and demonstrated fighting skills.

The citizens of Mazatlan knew what was coming and many chose to evacuate their homes and businesses, particularly those structures closest to the water.

The French warships arrived on November 12, 1864.

Sinaloa Governor Antonio Rosales and many of the Republican defenders knew they had no chance against the array of crack French troops aboard the ships -- and the naval cannon -- but when the D'Assas, Diamant and Victoire joined the La Cordelière off Mazatlan they were met by a delegation led by Governor Rosales, who attempted to finesse the situation and open negotiations.

The French infantry commander, Captain Thomas Louis Le Normant de Kergrist, was having none of it: he issued an ultimatum for surrender of the port that had a deadline the following day.

Written notice was given to the Mexican commanders that any resistance would result in immediate hostilities, and that neutral -- mostly American -- ships in the harbor would also be targeted should that occur.

Governor Rosales responded by putting his coastal batteries on alert with orders to fire on any ship coming within range.

Governor Rosales knew that he didn't have the military strength to defend the port and was determined to march north with his troops to El Habal and El Quelite, where they felt they could establish defensible positions from which to execute guerrilla operations against the French army and its Indian allies and mercenaries.

The French warships began firing early on the morning of November 13 -- arguably before the ultimatum deadline had expired -- and the shelling immediately damaged a number of buildings in the Centro Historico.

Governor Rosales and the Republican commanders could see firsthand the scope of damage that the French naval gunners could inflict if they continued firing.

The Governor and his senior commanders hastily sailed to the flagship of the French fleet accompanied by city leaders to inform the French commander that the General Corona had argued that the Republicans surrender -- and had evacuated his garrison as requested, fulfilling one of the terms of the French ultimatum.

They also offered formal surrender of Mazatlan and its port.

Martial law was immediately imposed by the French and the carrying of firearms and the trading of firearms were prohibited.

Republican units got out of Mazatlan just in time: heading north they were forced to fight a sharp engagement with Lozada's encircling Imperial forces that resulted in significant casualties.

Reaching El Quelite, the Republicans established defensive positions and a plan began to take form: Governor Antonio Rosales would command the Republican guerrilla forces in northern Sinaloa while General Ramón Corona would be responsible for southern Sinaloa.

Mazatlan was destined to endure an occupation that would last exactly two years -- the city was liberated on November 13, 1866.

The French occupation of Mazatlan from November 1864 to November 1866 was the longest in the city's history, and took place withing the context of the larger war between French and allied Imperial forces and the remainders of Benito Juarez's Republican government and military.

It also took place within the context of the French Imperial forces attempt to extend their military control throughout Sinaloa State -- particularly the parts of which where mines were located.

General Manuel Lozada's leadership had served France and the Empire of Mexico well in terms of the capture of the port and city, but administration of those assets and pressing the ongoing war in Sinaloa were another matter.

In early January 1865 a fresh French army marched from Durango to Mazatlan.

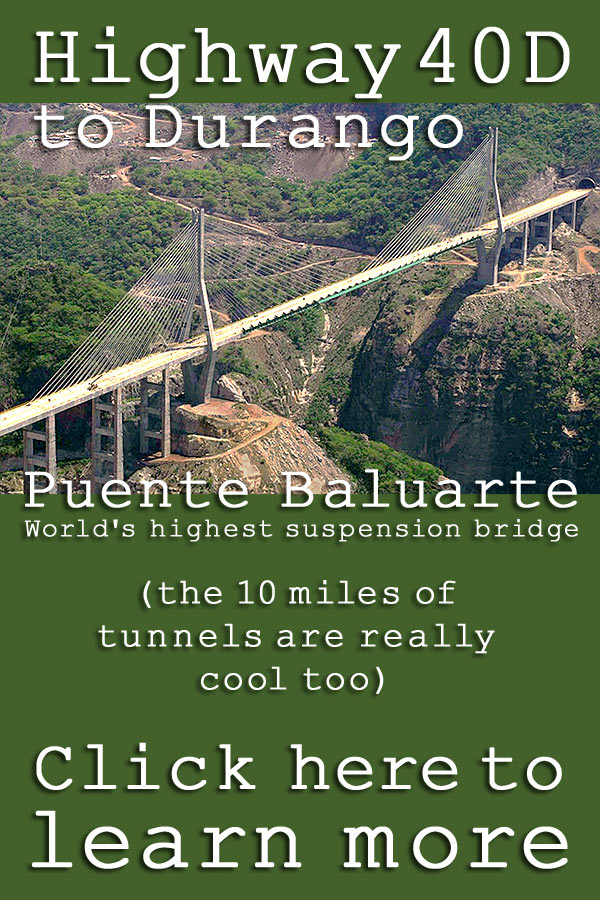

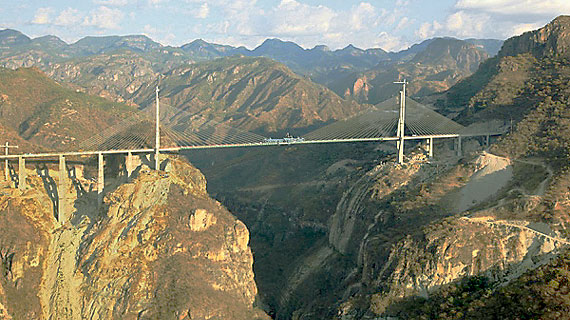

Following a route over the "Devil's Backbone" of the Sierra Madre Occidental that mirrors that of the modern Mexican Federal Highway 40 / 40D, General Armando Alexandre de Castagny and his troops got their first taste of Republican resistance near the Durango / Sinaloa border.

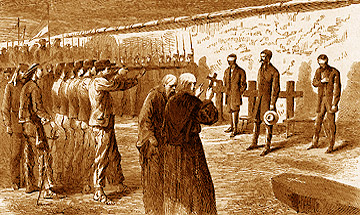

Though many Republicans died and the battle is regarded as a French victory, the experience was sobering and sewed the seeds of further bloodletting: a number of Republican prisoners were summarily executed -- and the Republicans knew it.

The French Imperial forces continued to advance toward Mazatlan and at the village of Veranos the Rebublicans ambushed them, this time with much more success, killing over 100 Cazadores de Vincennes and Regimiento de Zuavos soldiers -- elite French infantry who were veterans of the Battle of Puebla.

The bitter nature of the battles of The Second French Intervention in south-central Sinaloa was taking form: Republican units executed Imperialist prisoners in the village of Jacobo, Sinaloa, in retaliation for the executions at the "Devil's Backbone" just days before.

By late January 1865 French Imperial General Armando Alexandre de Castagny was firmly ensconced in a Centro Historico mansion, but local cooperation was, to say the least, disappointing.

General Castagny decided that a firm hand was what was needed, setting up military courts that were empowered to order executions of Mexican citizens.

The executions began just days later, on January 31, 1865.

But executions in Mazatlan alone weren't enough -- General Castagny had a war to pursue in the south Sinaloa countryside, and towns throughout south Sinaloa like Concordia, El Castillo, La Embocada, Malpica, Siquieros and Villa Unión were burned in punitive raids and -- on orders -- captured defenders were shot on the spot.

When a subordinate officer, Colonel Garnier, protested the actions, General Castagny dismissed him from the Imperial Army.

The Republican fighting forces and the civilian populations that supported them in south - central Sinaloa were exhausted by April 1866.

The majority of the important south-central Sinaloa towns had been looted and burned; the fields were unplanted; the cattle, pigs and poultry had been stolen; the few remaining horses were dying due to lack of fodder and everyone -- soldier or civilian alike -- was hungry.

But America's darkest day, April 15, 1865, had ironically be the beginning of a new dawn for Mazatlan and all of Mexico -- whether that was recognized in Mazatlan at the time or not.

The position -- and actions -- that the United States would take with regard to the French Intervention in the Americas of the 1860s were always a consideration for Napoleon III and Maximilian I, but were discounted by both because of the American Civil War and the limitations it put on the actions of President Abraham Lincoln.

It was clear that President Abraham Lincoln and much of the government of the United States had been sympathetic to Benito Juárez and the republican Mexican Government in 1864: Lincoln refused to recognize Maximilian I, and formally opposed the French invasion, but the titanic struggle that was the American Civil War prevented him from doing anything concrete -- just as Napoleon III had predicted.

When Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox the world changed for the French Imperialists, and not for the better.

Maximilian I attempted to diffuse American sympathy for Mexico by first offering Juárez amnesty and later the post of Prime Minister, but Juárez refused both saying that he would not support a government "imposed by foreigners" or a Mexican monarchy of any type.

The combined forces of the Mexican monarchists and the French Army won numerous battles in 1864 and early 1865 -- including those in Sinaloa -- but in the second half of 1865 the tide began to turn against them, in part because the American Civil War had ended.

After Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on April 15, 1865, his successor, US President Andrew Johnson invoked the Monroe doctrine and demanded that the French evacuate Mexico -- but in war-weary America congressional support was lacking.

When Johnson failed to get support in Congress in late 1865, history suggests that he clandestinely ordered the Army to "lose" military supplies near the border with Mexico where Benito Juárez' guerrilla fighters could pick them up.

By 1866 Johnson felt able to order the open use of military force: with the American Civil War over the United States Navy was freed up, and in February 1866 the United States imposed a naval blockade of French-occupied Mexico.

The military situation in Southern Sinaloa in mid 1866 is a perfect microcosm of the position Emperor Maximilian I found himself in throughout Mexico at that moment.

Within Sinaloa, the French controlled a major city and the major port which were, of course, the same place: Mazatlan.

But outside Mazatlan in the Sinaloa countryside, Republican guerrillas owned -- or could own if they chose to do so -- most of the roads. Without unfettered access to roads, the French could not be said to "control" Sinaloa at all.

Facing a blossoming guerrilla war and a financial catastrophe, Maximilian I became increasingly depressed. Napoleon III had known that the war in Mexico was lost for months by mid 1866, and was facing a mounting military threat in Europe from Prussia. Not willing to challenge the American blockade, he had begun quietly withdrawing French troops from Mexico soon after the blockade was announced.

As 1866 wore on, General Ramon Corona's south Sinaloa guerrilla army was strengthening, with arms smuggled south from the United States and captured weapons equipping ever increasing numbers of soldiers.

Just in the general neighborhood of Mazatlan, 1866 saw battles at Atravesada, Concordia, El Camarón, Las Higueras, Los Callejones de Barrón, Venadillo, Veranos, Villa Unión and Urías -- plus countless unnamed firefights and ambushes.

By Fall 1866, General Manuel Lozada had switched sides -- Emperor Maximilian I hadn't been paying him or his troops for several months -- and the defeat of the French garrison at Mazatlan had become only a matter of time.

On November 13, 1866, two years to the day after French occupation, General Ramon Corona expelled Maximilian's French Imperial Army from Mazatlán, and colonial rule in The Pearl of The Pacific was ended -- as was the entire French colonial adventure in Mexico the following year.

The last French strongpoint was La Garita de Palos Prietos, just north of the Centro Historico. The Republican guerrilla army took Palos Prietos by bayonet, and French defenses in the Centro Historico and the port collapsed almost immediately.

The French army left Mazatlan by ship -- as it was doing from several Mexican ports at the end of 1866 -- but Maximilian I refused to leave Mexico, and continued to fight Benito Juárez' growing partisan army.

In 1867 the last of Maximilian I troops were defeated and -- history suggests in retaliation for his orders earlier in the conflict to execute Republican prisoners of war -- he was sentenced to death by a military court. Despite international and domestic pleas for amnesty, Benito Juárez refused to commute the sentence.

The disaster of the Mexican Intervention was a humiliation for Napoleon, and he was widely blamed among European royals for Maximilian's death -- which was unjust because letters show that both Napoleon III and King Leopold of Belgium had warned Maximilian not to depend on European support.

The consequences for France of the defeat in Mexico were enormous: six thousand French soldiers died in the conflict; the war had cost over 330 million francs, it had aroused hostility both in the United States, which felt the Monroe Doctrine had been disrespected, and in Austria, which had lost a member of its royal family; and it weakened France on the eve of its coming war with Prussia.

In describing the French adventure American president Andrew Johnson invoked the Monroe Doctrine which said that efforts by European governments to interfere in the Americas would be viewed by the United States as acts of aggression requiring United States intervention.

President Johnson's assertion that European meddling in Mexico would be met by United States military force under the Monroe Doctrine turned out to be hollow -- at least with regard to Mazatlan and military actions in the Americas that weren't really government sanctioned.

Historians believe that the motives that drove Bridges' actions were petty and personal -- the captain apparently resented that local customs authorities had seized a small amount of gold from his ships' paymaster when on shore leave.

The effects of the naval blockades Mexican ports in the mid 1800s reverberated through the federal government in Mexico City.

Mazatlan and had not been the only port to be captured by American naval forces during the Mexican - American War of 1846 -1848 and the French Colonial Occupation of 1864 - 1866.

Guaymas, Sonora, an important port just north of the Sinaloa border, Veracruz and Tampico on the Gulf Coast and many other important harbors had been occupied by the Americans or French -- or both.

The Mexican federal government responded by passing a law in July 1867 which forbade state capitals from being located in ports. It took six years to implement, but in 1873 the state legislature of Sinaloa voted to relocate the capital from Mazatlan to Culiacán, which is inland.

Mazatlan's dramatic economic expansion was particularly robust under President Porfirio Díaz, a soldier turned politician who served seven terms as President of Mexico and governed for nearly three decades: one month in 1876; from 1877 to 1880; and from 1884 until he was forced out of office in 1911 at the start of the Mexican Revolution.

Díaz is a complex character in Mexican history and, as the last Mexican president prior to the revolution, was the target of the revolutionaries anger.

History paints a more nuanced picture.

Still something of a hero in the business community, the decades that Díaz was is office were marked by increased internal security, industrial modernization, and sustained economic growth. Substantial foreign investment in mining and railways were of particular benefit to Sinaloa State, and Mazatlan realized a large portion of those economic benefits.

Porfirian-era prosperity was, however, wildly unevenly distributed.

The creole class, pure-blooded descendants of Spanish settlers born in Mexico, benefited the most from Diaz's rule -- he generally handled wealthy creoles with kid gloves and was conspicuously careful not to interfere with their business dealings and financial assets, particularly landholdings.

The Catholic church's assets and perogatives were also left largely untouched -- which is somewhat surprising for two reasons.

The situation for many rural and lower-class Mexicans, indigenous Indians and members of other lower castes, was quite different. For them, the Porfirian Era was a mutli-generation disaster, with large-scale appropriations of land becoming widespread, commonplace, occurrences.

As in any economy with a labor shortage, migrants began to flow into Mazatlan and elsewhere in Sinaloa to fill the void.

In addition to Europeans, Chinese, Japanese and other Asians began arriving at the Port of Mazatlan in the late 1800s, drawn by jobs and seeking economic betterment.

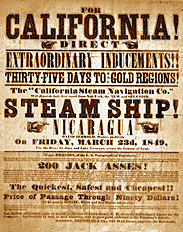

Other economic migrants were flowing to Mazatlan -- even if only to pass through.

During the California Gold Rush of the late 1800s prospectors from the United States sailed from east coast ports to Mexican ports in the Gulf of Mexico, notably Veracruz.

History clearly records that most, of course, failed to realize their golden California dream, but every miner that passed through Mazatlan supported our economy, and the growing strength of the municipality.

The fruits of this economic activity could be seen all over Mazatlan.

In 1879 Mazatlan's unique and majestic lighthouse -- El Faro -- first cast its glorious light westward over the Pacific ocean.

To this day the tallest lighthouse in the Americas, El Faro's original oil lamp was fabricated in Paris and was focused with mirrors and a Fresnel lens. Since the light did not move it was often mistaken for a star.

In 1883 Angela Peralta, a Mexican opera diva, died of yellow fever in The Pearl of The Pacific shortly after her arrival in the port. History -- based on local legend -- has it she sang one last aria from the balcony of the Hotel Iturbide, overlooking Plaza Machado.

Her memory is held dear by Mazatlecos to this day, and the restored Teatro Ángela Peralta immediately beside the Plaza Machado keeps the history of her fatal visit and her memory alive -- as well as providing modern-day Mazatlan with a truly world-class performance venue.

The increasing prosperity of the late 1800s and early 1900s Mazatlan saw many advanced civic amenities like electrification, street lights, city water systems and modern large-scale markets usually associated with larger or European cities began to emerge.

But even occasional false-starts like Ferrocarril Urbano de Mazatlan do not overshadow the enormously rapid pace of development in Mazatlan in the late 1800s including city water and electricity, the construction of Mercado Pino Suarez -- a state-of-the-art massive ironwork market -- and, of course, Carnival...

Nothing is more important to the development of a city than a reliable source of potable water and, for residents in the mid and latter 1800s, potable water supply in Mazatlan was often a problem.

The simplest explaination is really a history of Urban Planning 101 -- rapid population growth had far outstripped supply.

Mazatlan is not really blessed with easy-to-access sources of freshwater.

Traditionally, early settlers in Mazatlan harvested rain water -- which is fairly plentiful with over 30 inches annual rainfall -- and kept it in cisterns for the long periods of the year where there is little or no rain. By the 1860's there were supposedly over 125 private cisterns with a combined capacity of over 50,000 liters.

It simply wasn't enough and, as the population of Mazatlan grew, water hauling -- bringing water from local lagoons and water holes -- became another (highly innefficient) part of the water supply mix.

At least the rain water was probably pretty clean, even after being stored in a cistern.

The hauled water, on the other hand, was almost universally from brackish sources, smelly and often unhealthy. The delivery mechanism was donkeys with five liter clay jugs being led through neighborhoods.

There were two aborted plans in the 1800s designed to improve the water supply in Mazatlan.

The first, in 1863, was a study by the government of the city of Mazatlan, supported by Sinaloa Governor Placido Vega, for a municipal water system. The plan went nowhere.

The second, in 1881, involved an interesting scheme that would have placed water pumping facilities on Stone Island, and piped the water to the southern end of the city. Despite great fanfare, for both engineering and financial reasons that plan went nowhere as well.

In 1887 - 1888 a solution arrived in the form of an enterprise jointly owned by some of the wealthiest merchants in Mazatlan.

Francisco Echeguren y de la Quintana, H. W. Felton, Julián Mendía, Antonio Paredes, Luis Reynaud and Bernardo Vázquez -- along with other wealthy merchants -- formed Compañía Abastecedora de Agua de Mazatlán, which was destined to become a privately owned monopoly water supplier to the city.

This group had done its homework. On October 16, 1886 -- prior to the formal establishment of the company -- the investors had submitted to the City Council a request that the Council ask the Congress of Sinaloa for a tax exemption for all materials that they would have to import from the United States.

The shopping list was substantial, including over 20 miles of iron and steel pipe; over 100,000 pounds of lead for soldering; materials and equipment to build 4 steam boilers; and all of the valves, pumps and joints to stich all of this together into a working water system.

By June 1887 the tax exemptions had been granted. The deal granted Compañía Abastecedora de Agua de Mazatlán exclusive rights to supply water to the City of Mazatlan for 99 years; granted the company the right to use vacant lots owned by the city -- and even to appropriate private property -- as locations for tanks and pumping stations; permitted it to harvest water from nearby rivers and streams; and freed the company of any municipal tax obligations for 50 years.

It also called for the work to be completed in 20 months.

In August 1887 the company was incorporated by shareholders Francisco C. Alcalde, Martín Careaga, E.G. Felton, Genaro García, Pablo Hidalgo, Federico Koerdell, Lauro Wall and, perhaps most importantly, Alejandro Loubet of Loubet and Guzman, the premier foundry in Sinaloa responsible for both the engineering and fabrication of the boilers.

The aquifer identified as the primary source of Mazatlan's first municipal water system was in a small village on the Rio Presidio. Construction of two large holding tanks on Cerro de Peña Hueca -- a hill near today's Siquieros Dam -- was begun immediately on land appropriated from the family of Antonio Vico.

These tanks have a combined capacity of 17,000 cubic meters, and remained in use for over 75 years, only being decomissioned when alternative sources of water in the towns of San Francisquito and El Pozole went into operation in the mid 20th century.

Further land appropriations followed with over 110,000 square meters handed over to the water company in September 1887 and the additional appropriation of a substantial part of Cerro de Casa Mata in August 1888.

While the job didn't get done in the twenty months projected, but on the night of May 4, 1890, for the first time in history Mazatlan had city water.

The first flow had a reddish tinge, looked oily and had a strongly metallic taste -- and the City Council was forced to issue an urgent statement which explained to the community that this did not imply any risk since it was caused by sediments left in the pipes from construction and would disappear once water had flowed through them for a while.

1881 marks the year that streetlights and city electrical grids were born -- in Surrey, England -- but most humans, even urban humans, lived entirely without electricity in the late 1800s and even in the 1900s.

Mazatlan was an early adopter of urban electrical streetlights and electrical grids -- the first such system was switched on in 1896.

The financial origins of that system may seem ironic to a modern reader -- quite unlike today, in late 1800s Mazatlan electricity was far less expensive that the natural gas that fueled gas street lamps!

For those who like continuity of cash flow, it is comforting to know that Jesús Escovar, the owner of Compañía de Gas Hidrogeno -- the company that had supplied the gas lamps since mid 1868 -- got the contract for electrification.

Some of the earliest areas to get the new electric street lights were Plaza Machado and Plaza Hidalgo, along with the southern portion on the Malecon.

The first major streets that had electric lighting were Angel Flores, Belisario Dominguez, Benito Juarez, Canizales, Cinco de Mayo, Constitucion, Marzo 21, Melchor Ocampo, Sixto Osuna and Venustiano Carranza.

Wires from this newborn electrical grid were rapidly run to wealthy families homes -- which many considered a blessing because gas and oil lamps and candles were substantial fire hazards.

Almost immediately -- and not unlike other cities in the late 1800s -- a second private Mazatlan electrical company was founded.

A very prominent Mazatlan entrepreneur, Arthur de Cima Leon -- owner of the ice company, the telephone company and the trolly company -- began running his own wires. By the end of 1896 he is reported to have had over 300 electrical service contracts, and was importing new electrical generation equipment.

The competition between Jesús Escovar's Compañía de Gas Hidrogeno and Arthur de Cima Leon's company was fierce for several years, including a history of acts of sabotage and vandalism by both company's workers -- as well as hired muscle.

Acts of vandalism were so frequent that both companies decided to make their staff wear uniforms to help customers, government authorities and the public in general to identify those who were damaging electrical installations.

Competition was ended when the companies merged in 1906 under the ownership of the upstart, Arthur de Cima Leon.

Electricity was successfully provided in Mazatlan by this private electrical company until 1937 when the electrical grid of Mexico was nationalized and became the Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE) we know and love today.

Mercado Pino Suarez was the solution.

Prior to the construction of the magnificent market you see today there were a number of largely open-air markets, notably in Plaza Zaragoza and Plaza de la Republica.

In the 1890s it was decided that, for both aesthetic and sanitary reasons, Mazatlan needed a modern central market, and the location between Benito Juarez and Aquiles Serdan was chosen.

The history of Mexico from the 1880s through the first decade of the 20th century is often referred to as the "Porfirian Era" after Porfirio Diaz, a soldier who was President of Mexico three times -- in total nearly three decades -- including the period from 1884 until his overthrow in 1911.

Porfirio Diaz was very enamored of many things French -- he chose France when he was exiled and died there in 1915 -- and the design of the Mercado Pino Suarez is heavily influenced by the late 19th century French ironwork aesthetic that was used in the Eiffel Tower and other important public structures in France during that period.

There are numerous remarkable statistics about the amount of iron that went into the Pino Suarez Market (estimated to be over 300,000 pounds) but simply consider this: each of the twenty-nine single-casting columns that the roof rests on are over thirty feet tall!

In 1915 the market was re-named Mercado José María Pino Suárez in honor of the Vice President of Mexico who was killed in 1913 during the darkest days of the Mexican Revolution.

Now home to over 250 tenants and employing nearly 1000, the Mercado Pino Suarez is a vibrant part of the Mazatlan shopping scene even in the era of supermarkets and big-box malls. LEARN MORE

Though Carnaval was noted in Mazatlan as early as 1848 -- it was mentioned in the Mazatlan newspaper La Lechuza -- it wasn't until 50 years later than the event took its present form as a seven-day multi-event blow-out complete with parades, floats, social events and an official King and Queen. History notes that the early Mazatlan Carnivals -- pre 1898 -- were informal and often somewhat vulgar, with women throwing flour and hollow eggshells (cascarones) filled with glitter, and men responding by tossing ashes and dyes at the women.

But in 1898 civic leaders headed by Dr. Martiniano Carvajal and a committee with an international flavor -- it supposedly included an Irishman, a German, a Spaniard and an Italian -- organized a parade made up of carriages and bicycles "to eradicate the immoral flour and replace it with the pure and more restrained confetti."

The modern Mazatlan Carnival may not involve tossing flour, but it is hardly restrained. Mardi Gras in Mazatlan is one of the biggest and best bashes anywhere in the Americas that sees thousands of costumed revellers thronging the Malecon and beaches.

Each evening the Malecon at Olas Altas Beach becomes the perfect stage for this singing and dancing Bacchanalia, with outdoor concerts, sound and light shows and beer for everyone! LEARN MORE AND READ ABOUT CARNAVAL 2020!

20th Century Mazatlán

In March of 1900 Jorge Claussen, German Evers, and Emilio Philipi created a partnership that became the Cerveceria del Pacifico brewery in Mazatlan. Their first product was Cerveza Pacifico Clara, a pilsner-style beer.

The beer became instantly popular in The Pearl of The Pacific, then Sinaloa State, and rapidly throughout Mexico.

Now known world wide as one of the finest Pilsners, Pacifico's brand is intimately associated with Mazatlan Mexico. Cerveceria del Pacifico -- now a part of Grupo Modelo -- remains a huge and interesting part of our business scene, and tours of the Pacifico Brewery and their museum can be arranged by telephoning 669 982 7900, extension 1642.

Video of the Pacifico Brewery in Mazatlan

The Tambora is played with a felt mallet. With its double headed membranophone, large diameter, and fixed cymbal, the Tambora is highly distinctive and unique to Mexican music. Tambora music, the traditional oompah band music of northern Mexico, is heard throughout The Pearl of The Pacific, especially at Carnaval and other holidays.

Despite impressive local economic successes, 20th century history brought turbulent times to Mazatlan -- and all of Mexico. The Mexican revolution stands as the watershed moment in Mexican history, and the true birth pain of the modern Mexican state.

The failed vote-rigging of the 1910 presidential election triggered the collapse of Porfirio Diaz's rule in 1911 marked the beginning of the revolution -- and subsequent struggles for power -- that created modern Mexico.

The Pearl of The Pacific did not escape the widespread destruction that visited all of Mexico.

Sinaloa played a major role in the Mexican Revolution, and was both the site of important military engagements and the staging ground for the Constitutionalist march south along the Pacific Coast toward Mexico City.

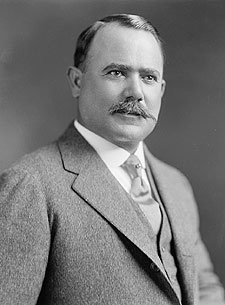

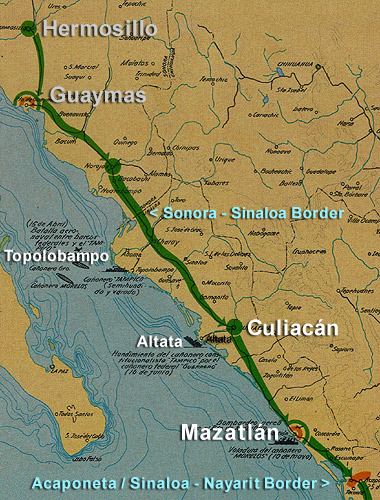

Obregón had achieved early military successes in Sonora in 1912 and had been appointed Commanding General of Sonora's War Department in March 1913 by Venustiano Carranza, the head of the Constitutional Army.

By early May, 1913, Obregón's ranks at his base-camp in Hermosillo, Sonora, had swelled to as many as 7,000, mostly Sonorans that had enlisted to fight Huerta's Federalist army.

Carranza's overall strategy for the capture of Mexico City -- the seat of national government -- had three axis' of assault, and divided command of the Constitutionalist armies among three Generals: Obregón, Francisco "Pancho" Villa and Emiliano Zapata.

Obregón was tasked with driving the Constitutional Army of Northwest Mexico down the Pacific coast following the railroad line that remains the primary corridor for heavy freight transport in Western Mexico to this day. His route-of-march was designed to take him south through Sinaloa, Nayarit, Jalisco, Guanajuato and Hidalgo states, driving on Mexico City after he had linked up with Pancho Villa's army at the city of Queretero.

Villa was to drive his army -- commonly referred to as the División del Norte (Northern Division) -- south through the center of the country following the central rail line that connects south-central Mexico with Chihuahua State. His route-of-march would take his army south from Chihuahua through San Luis Potosi and Guanajuato states, where he would link up with Obregón at Queretero and drive southeast for the final push on Mexico City.

Zapata -- formally Emiliano Zapata Salazar -- and his Liberation Army of the South were to build upon the rebellion that they had fomented across a large swath of Mexico that extended from the Southern edges of Mexico City to the Pacific Ocean. Zapata's insurgency was designed to sap Federalist resources and prevent them from further strengthening fortified positions they were creating in anticipation of the Constitutionalist armies drive south.

Obregón's Constitutional Army of Northwest Mexico was widely viewed as the most professional of the three fighting forces, and historians are in near unanimous agreement that Obregón was -- by far -- both the most talented and the most rational of the three generals.

October, 1913

His first goal was to invest and bypass the Port of Guaymas in southern Sonora, and deprive the Federalists of the use of its docks.

The mission in Sinaloa had four distinct primary objectives which were (in the order they would be encountered marching south)...

• To take and secure the port at Topolobampo.

• To take and secure the capital of Sinaloa State, Culiacan.

• To at least neutralize Federalist use of the Port of Mazatlan.

• To secure the primary north / south railroad and road corridor through Sinaloa.

Obregón was remarkably swift in his march south.

Under Obregón's leadership, the Constitutional Army of the Northwest marched through southern Sonora and Sinaloa in slightly less than six months -- the campaign lasted from late October 1913 until April 1914 -- and exited the southern end of the state on April 25, 1914 where it engaged Federalist forces at Acaponeta, just five miles across the border in Nayarit State.

This represents an average rate of march of over three miles per day, a remarkable achievement for any army in history operating with virtually no mechanized transport.

The longest delay caused by battle within Sinaloa State was the nine day fight at Culiacan that lasted from from November 5 to November 14, 1913.

Prior to the battle at Culiacan, Obregón had already invested the Port of Guaymas in southern Sonora; secured the highway / railway junction city of Los Mochis; secured the capital of northern Sinaloa, El Fuerte; and -- perhaps most importantly -- taken the Port of Topolobampo, opening its docks to be used to re-supply the Constitutionalist Army.

But looming in the path of Obregón's advance was a significant obstacle: the Port of Mazatlan and its historically robust fortifications.

Obregón was being watched not only within Mexico, but by the world. Beginning at the end of December, 1913, the Japanese cruiser Izumo and the German cruiser SMS Nürnberg were prowling the waters of the Sea of Cortez just off the port, ostensibly to be ready to protect the property and safety of the many Japanese and German immigrants living in Sinaloa.

Because of both Mazatlan's importance as a gateway for Federalist supplies for its forces fighting in northwest Mexico and the history of the port, Mazatlan was much better defended than Culiacan.

The Federalist troops stationed in Mazatlan were better equipped and better trained than those that Obregón had defeated at Culiacan or the Port of Topolobampo.

Centuries of military presence in Mazatlan -- and the centuries-long history of military engagements there -- had left a legacy of robust military fortifications, as well as a substantial body of military knowledge about how to effectively defend land approaches to the city.

One thing was, while difficult to accept, clear to Álvaro Obregón: a frontal assault on Mazatlan was not a rational option. He decided to employ the tactic that had served him so well at Guaymas: simply bypass the port altogether.

By early April, 1914, Obregón had largely completed his encirclement of Mazatlan from the landward side.

While some supplies were still flowing into the port, which the Constitutionalists lacked the naval resources to seal, Mazatlan was cut off from its primary sources of ammunition, food and, most importantly, water.

The water shortage was particularly dire as the result of the Constitutionalist seizure of wells and storage tanks at Peña Hueca -- then and now an important source of water for Mazatlan -- as they tightened their grip on the port. Thirsty Mazatlecos re-opened both public and private wells that had been abandoned, and new trench wells were dug in the southern part of the city in a desperate attempt to find water.

The increasingly desperate population of Mazatlan grew increasingly unruly, with major merchants' warehouses looted by mobs in search of food they thought was stored within them -- which turned out to mostly be untrue -- and with Chinese merchants being particularly hard-hit.

Obregón was committed to maintaining the timetable and responsibilities that his Constitutional Army of Northwest Mexico had to the overall strategy designed to defeat Federalists throughout Mexico, but Mazatlan, the top strategic prize in Sinaloa, was not forgotten.

While Obregón, personally, left Mazatlan in late April and moved his army south into Nayarit State, he left a substantial number of troops and weapons to ensure that Mazatlan remained blockaded by land, and to sustain the pressure on the population and Federalist forces to surrender.

In addition to the troops left behind to maintain the seige under the command of General Ramón Iturbe, Obregón even committed his one substantial remaining naval asset in the Sea of Cortez -- the gunboat Tampico -- to its ill-fated final mission in mid-June in an attempt to put her to some use against the Federalist Navy operating off the Port of Mazatlan and elsewhere along the Sinaloa coast.

He also decided to deploy air power -- which he had first experimented with in the naval battles at Topolobampo on April 9, 1914 -- to put further pressure on the Federalists in Mazatlan.

While ineffective, the incident convinced Obregón that aerial bombardment could be useful to his army. Far from being discouraged by the failure of the Sonora to do damage to the General Guerrero at Topolobampo, Obregón believed that he had seen a new military weapon being born -- and had ideas how to improve it.

Obregón had another target in mind, the Federalist troops that occupied Mazatlan, and had found help designing better bombs and bombing techniques in the form of foreign aviators and mechanics sympathetic to the Constitutionalist cause.

The new bombs were considerably more sophisticated than those use during the air raid on the General Guerrero.

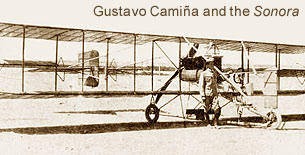

Fabricated in Navolato, Sinaloa, they were dynamite sticks surrounded with small bits of iron and steel designed to create a lethal hail of shrapnel when they exploded. On May 6, 1914, Gustavo Salinas Camiña took off with Teodoro Madariaga, carrying several bombs of this type hanging under their airplane.

The mission was to drop them on Federalist troops, but a navigational error caused the airplane to deviate from its planned path.

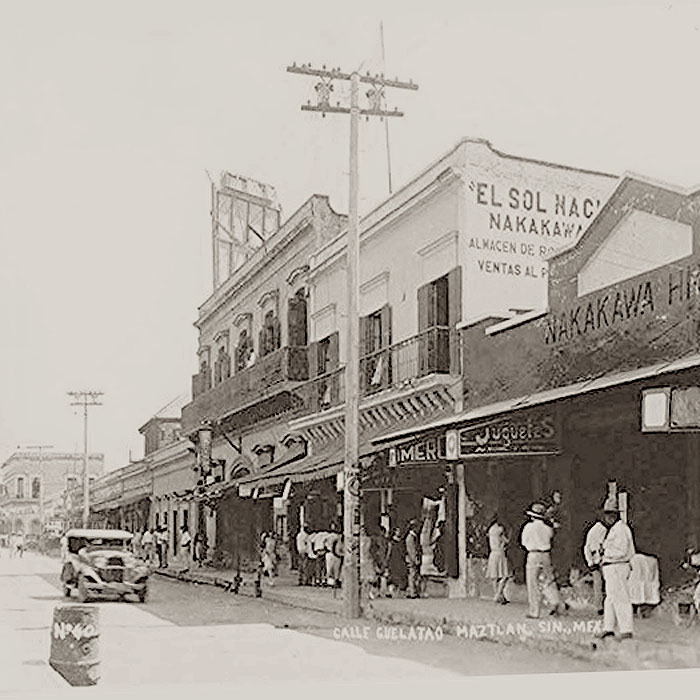

One of the bombs fell on a crowded housing and commercial area between Calle Ocampo and Calle Carnaval. The photograph to the right shows Calle Carnaval just moments before the bombs were dropped.

They caused severe damage to the French consulate, wounded the French counsul, and destroyed a number of houses.

In total, the air raid killed four and wounded fifteen, all civilian residents of Mazatlan.

The death and injury of civilians by aerial bombardment was unprecedented in Mexico -- and had only happened once before in Tripoli, Libya -- and consuls from several countries asked General Obregón to cease aerial bombardment of Mazatlan on humanitarian grounds and to create a safe zone for civilians.

Obregón agreed, at least with regard to purely civilian locations. Fortified positions were, however, a different matter.

Just a week after the civilian deaths in Mazatlan Salinas and Dean attempted to drop bombs on a number of fortified positions within the city and near the port.

A bomb aimed at the fortification in Loma Atravesada fell harmlessly within the railroad yards, but another fell on a group of Federal soldiers who had gathered to watch the airplane, causing several casualties, and another bomb destroyed an 80mm cannon, killing its eight man crew.

By Summer, 1914, the Constitutionalist Air Force was receiving new aircraft and pilots, and Constitutionalist planes continued to attack Federalist gunboats operating out of other ports.

The aerial bombings in Mazatlan and elsewhere in Sinaloa later in 1914 clearly demonstrated that the days of ineffectual aerial bombardment were rapidly coming to a close, not just in Mexico, but worldwide.

The resignation of Federalist President Victoriana Huerta on July 15, 1914 and his subsequent flight from Mexico was a huge blow to Federalist morale throughout the parts of Mexico they controlled.

Foreign consuls in Mazatlan including representatives from Chile, England, France, Germany and Spain tried to use the moment to negotiate a peaceful settlement in Mazatlan, but meetings held on neutral United States Navy ships anchored just outside the port proved fruitless.

By early-August, 1914, General Ramón Iturbe and his senior commanders Generals Juan Carrasco and Macario Gaxiola were ready to make a final assault on Mazatlan.

Fighting broke out on August 4, 1914, at Olas Altas beach, and quickly spread to other areas as Constitutionalist troops advanced and Constitutionalist commanders, notably General Juan Carrasco and Lieutenant Colonel Juan Ramón Rangel, scored early tactical successes.

August 5 through August 7, 1914, saw the Federalist troops occupying Mazatlan in increasing disarray -- while there were many sharp firefights, the Constitutionalists took some important positions largely unopposed, the Federalists troops having fled in advance of battle.

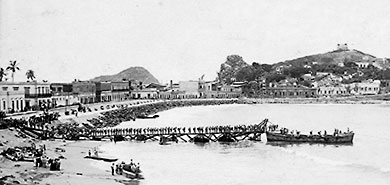

The Constitutionalist advance was rapid, and increasing numbers of Federalist troops were withdrawing to a hastily constructed temporary pier that had been assembled at Olas Altas beach in order to allow troops to board rescue boats.

A number of Constitutionalist officers destined for larger roles later in the Mexican revolution distinguished themselves in the battle to free Mazatlan, notably Colonel Ángel Flores, who was promoted to Brigadier General and later served as Governor of Sinaloa State from 1920 to 1924.

When Captain Guillermo Nelson captured Colonel Francisco Reynoso and his 17 Federalist troops at the pier at Olas Altas beach it was effectvely all over: the Constitutionalist forces controlled the entire port.

Federalist General Miguel Rodríguez fled Mazatlan in the gunboat General Guerrero, along with nearly 100 other Federalist officers and frightened civilian sympathizers.

The seething resentment of the part of the population who had opposed the Federalist occupation was perfectly blended with the natural anger of victorious soldiers just after battle.

The consequences for Federalist prisoners of war, and even civilian Federalist sympathizers, were dark. The execution of a number of Federalist officers -- including those of relatively high rank such as Colonel -- was coupled with the execution of Federalist officials, and even some Mazatlecos who were just "denounced" as having been collaborators.

The battles of the Mexican Revolution that took place in Mazatlan August 4 - 9, 1914, were fierce urban street fights, and casualties were substantial.

Constitutionalist casualties are reported to have been over 200 dead, with over 250 wounded.

Federalists casualties were far worse: more than 400 dead, over 500 wounded, and over 300 captured.

Civilian casualties are unknown but, given the nature of urban warfare, are likely to have been significant.

But the Great Depression put and end to that.

No economy anywhere in the world -- especially an economy as dependent on world economic health and free international trade as is that of a port -- entirely escaped the ravages of the Great Depression.

But despite the massive global economic shock of the Great Depression, Mazatlan continued to grow, its importance as Mexicos' largest Pacific coast port and economic center of Sinaloa State continuing to underpin its economy.

Video of 1920s Mazatlan

Although both Germany and Japan made overtures to Mexico and did purchase some oil in 1939 from the newly nationalized oil company -- now Pemex -- by 1940 it was obvious that Mexico's interests lay with the United States and the Allies.

1940-41 witnessed elections in both the United States and Mexico, with Franklin Roosevelt being re-elected to a third term in the United States, and Avila Camacho elected to the Mexican presidency. History records the bitter disputes surrounding the Camacho election, with the right-wing Spanish fascist connected candidate Juan Andreu Almazan going so far as to have supporters in the United States obtain weapons intended for use in an armed rebellion.

Roosevelts' early and strong support for Camacho -- along with his use of the F.B.I and United States military intelligence to assist the Mexican Army in the struggle against the pro-Almazan forces -- cemented ties between the two leaders, and paved the way for greater cooperation as WWII unfolded.

The breaking point came in May, 1942, when the Mexican oil tanker Potrero del Llano was torpedoed by the German submarine U-564 off Miami, killing 14 members of its crew.

Just days later -- and after the attack on a second ship, the Faja de Oro, which was torpedoed and sunk while on a voyage from Philadelphia to Tampico by the German submarine U-106 -- Mexico declared war on Germany and the Axis powers.

The denial of Mexico -- and Mazatlan -- as a safe harbor for Nazi submarines was of historical importance to the Allies war efforts.

Mexico also helped the Allies in other ways. Mexican oil helped fuel United States war industries, and other Mexican raw materials were vital to the United States warfighting efforts in WWII. With many millions of American men in the United States armed forces and thousands of American women working in factories, Mexican labor -- mostly in the form of agricultural workers -- was central to sustaining and increasing agricultural production in the United States during WWII.

The historic 1943 Mazatlan hurricane was a powerful tropical cyclone that struck the Pacific coast of Mexico in October 1943. The hurricane made landfall just south of the Centro Historico on October 9 and had sustained winds of over 130 mph. At least a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, the 1943 Mazatlan hurricane was the strongest hurricane in The Pearl of The Pacific's recorded history.

It is one of only two truly major hurricanes to strike in the entire recorded history of Mazatlan, the other being the equally devastating Hurricane Olivia in 1975.

History records that the hurricane destroyed about half of the buildings in Mazatlan, and near the ocean the combination of strong waves, high winds, and rainfall left many hotels and houses heavily damaged, as well as destroying much public infrastructure.

The storm severely damaged Mazatlan's water system, leaving many areas without potable water or sewage systems. The 1943 hurricane severely impacted transportation and communication infrastructures, with the airport sustaining damage to numerous buildings including the radio tower.

For at least eighteen hours the only communication between Mazatlan and the rest of Mexico -- and the world -- was through a battery powered radio in an airliner that had been forced down at the airport.

of a northwest Mexico tourist destination in

southern Sinaloa

Partly as a result of the media exposure that came along with these these famous visitors, hotels along Olas Altas Beach and the Malecon did well during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

They were supported by sport fishing tourism, as well as many other tourists both from both outside and inside Mexico who had discovered Mazatlan's charms.

The Freeman was constructed in 1946 and the La Siesta in 1954 -- and both remain some of the best choices a tourist can make when choosing lodging in Mazatlan!

The steady growth of tourism in the 1950s fueled continued infrastructure improvements and brought visitors from increasingly far-flung places, many of whom chose to purchase real estate and become part or full-time residents.

Video of Mazatlan in 1962

By the early 1970s Mazatlan was booming, and had even begun to rival Acapulco -- the darling of Mexican tourism in the 1960s -- as a vacation destination on the Pacific coast of Mexico.

The hurricane that devastated Mazatlan came as a surprise: the 1975 hurricane season had been a non-event up until that point, with all of the previous storms tracking northwest away from the coast of Sinaloa and largely even missing the southern tip of the Baja peninsula.

Olivia was disasterously different.

On October 23, 1975, the storm intensified, turned to the northeast -- and accelerated.

By October 24 reconnaissance flights reported sustained wind speeds of over 90 mph, and ships caught in its path radioed that the sea was extremely rough.

Warned by Hurricane Hunter aircraft flights and satellite imagery, the Sinaloa State government and the Mexican military had evacuated roughly 50,000 people from low-lying and other vulnerable areas.

Their efforts to protect the citizens of Mazatlan were only partially successful. Over 30 Sinaloans were killed by Hurricane Olivia, and heavy wind and torrential rain destroyed over 7000 homes in Mazatlan and nearby villages.

Downed trees and other storm debris littered streets, and electrical power was cut throughout the Municipality of Mazatlan. The Mazatlan airport -- which had been closed as Olivia approached -- was heavily damaged. The terminal was in ruins and many parked aircraft were destroyed. High winds collapsed a wall at a the municipal prison, killing two inmates and creating an opening that allowed other prisoners to escape.

Tragedy struck at sea as well: twenty sailors were lost on three shrimp boats that failed to make port before the storm hit.